Porsche's 959 Paris-Dakar

Over the past few months Porsche Heritage and Museum teamed up with their colleagues from Porsche Classic to recommission a rally raiding legend, a car that survived over 8,500 miles in the deserts and savannahs of Africa. The Porsche 959 Paris-Dakar mastered the gruelling rally from France to West Africa in 1986. The 959, in which Jacky Ickx and Claude Brasseur finished second behind the winning French team of René Metge and Dominique Lemoyne – in an identical car – is now ready to by driven once again.

The starting line-up of the Paris-Dakar Rally in 1986 was dominated by trucks and all-terrain vehicles. The three Porsche 959 cars from Zuffenhausen stood out – the third, a service car driven by project manager Roland Kussmaul and Wolf-Hendrik Unger, took sixth place. To this day, the Porsche Museum has preserved the complete trio as part of its collection. “The winning car remains untouched and we keep it in a kind of time capsule, so to speak, with all of the physical traces of the rally preserved for as long as possible,” explains Kuno Werner, Head of the Museum Workshop.

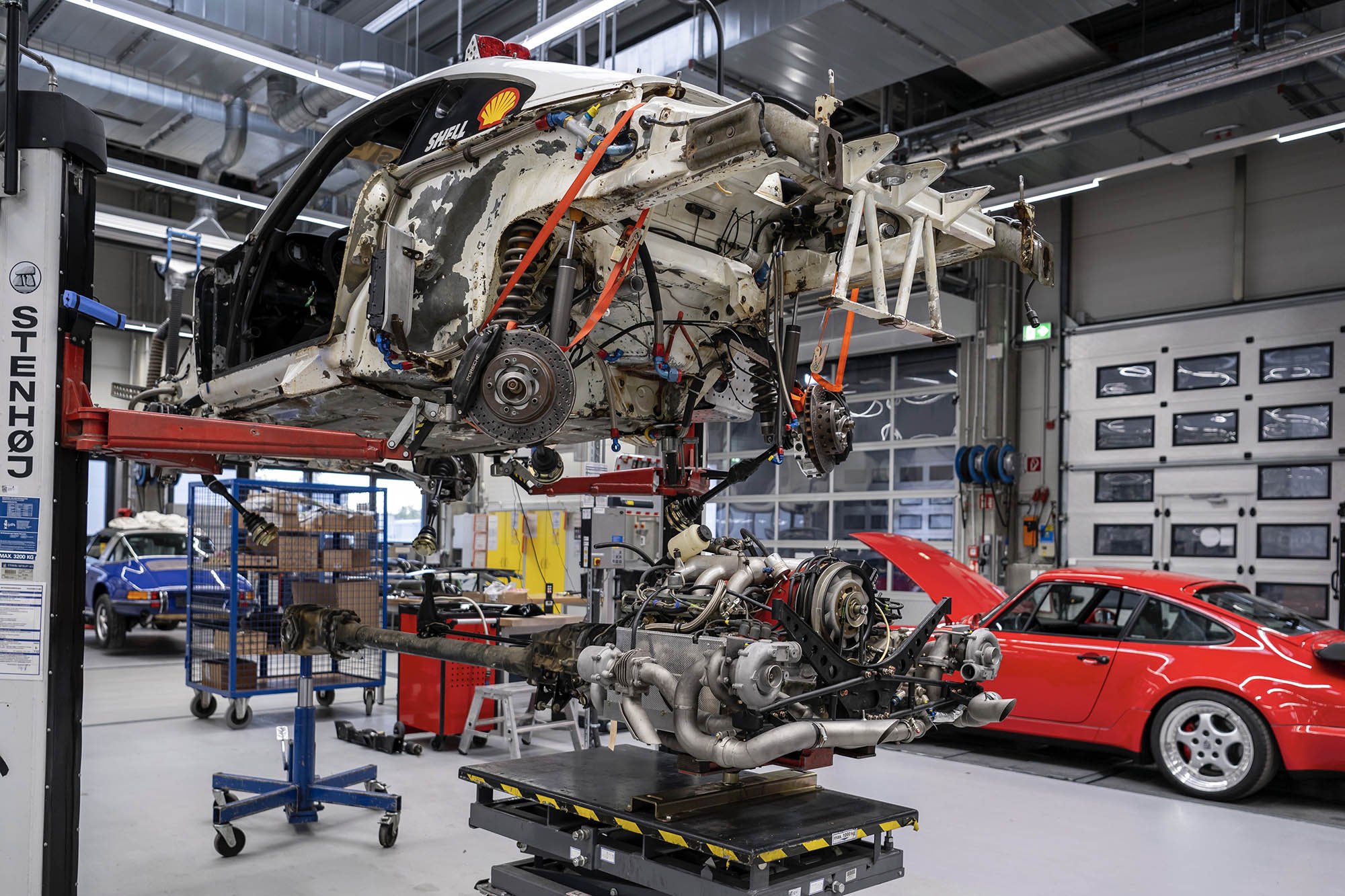

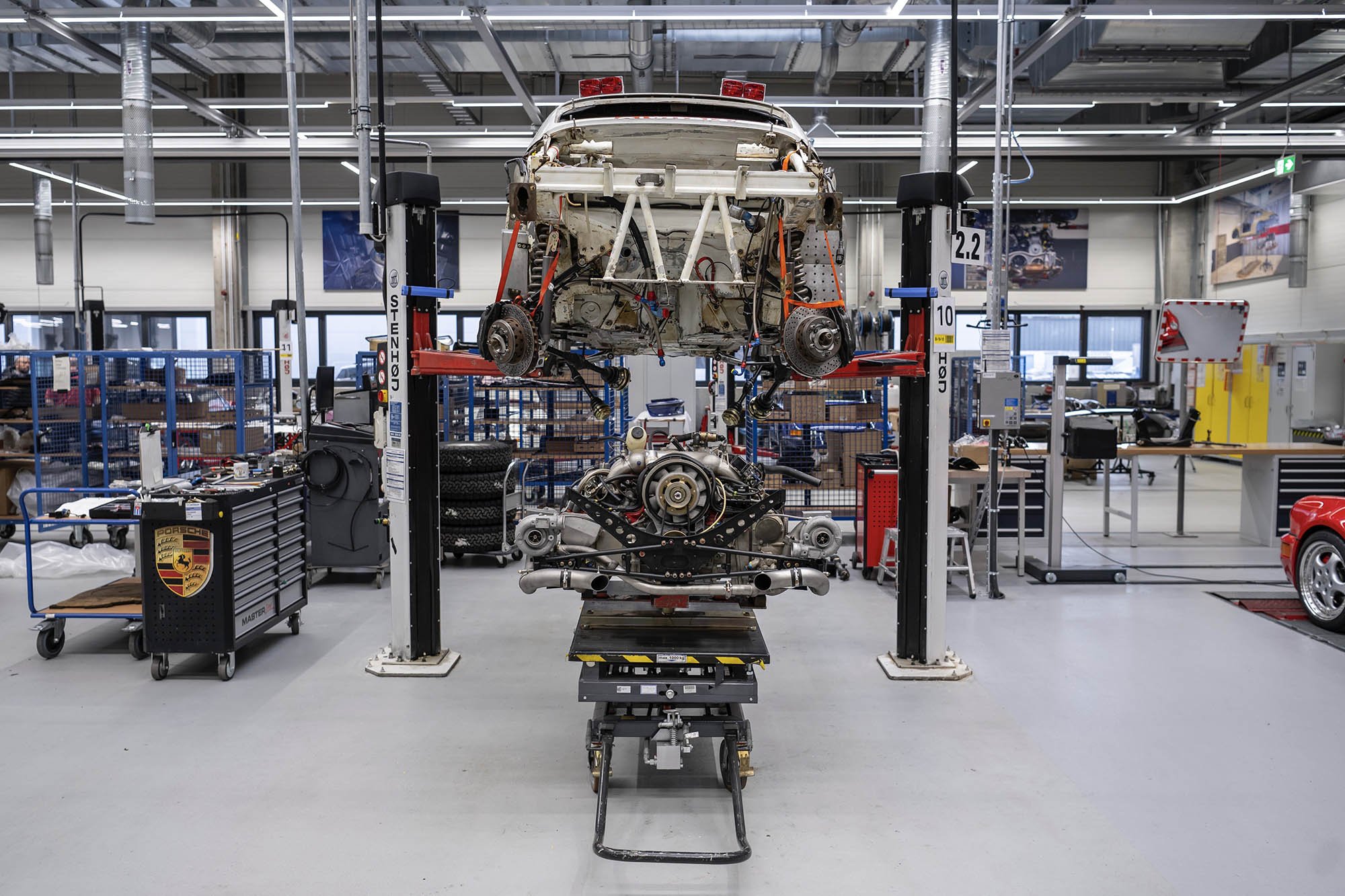

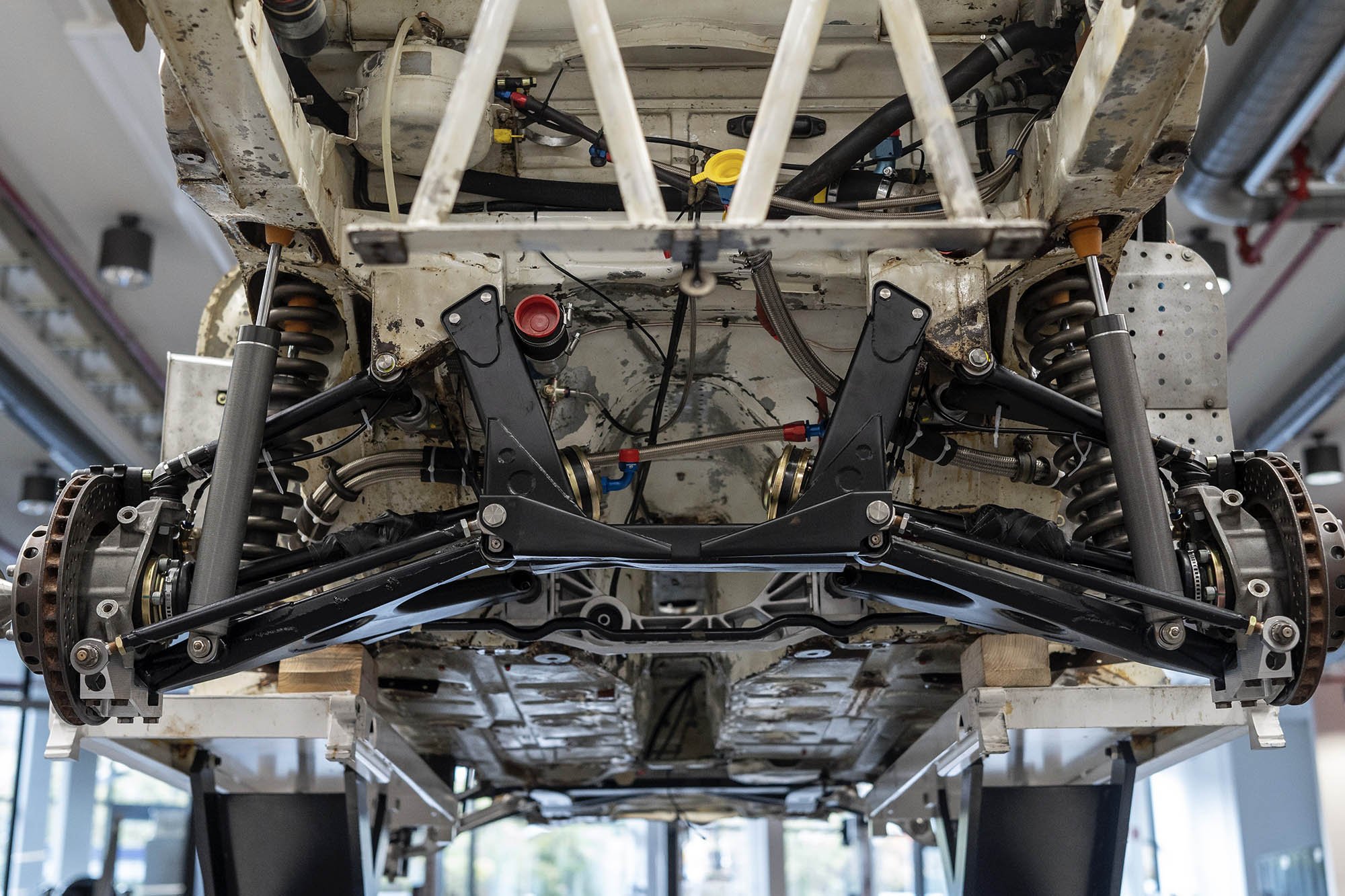

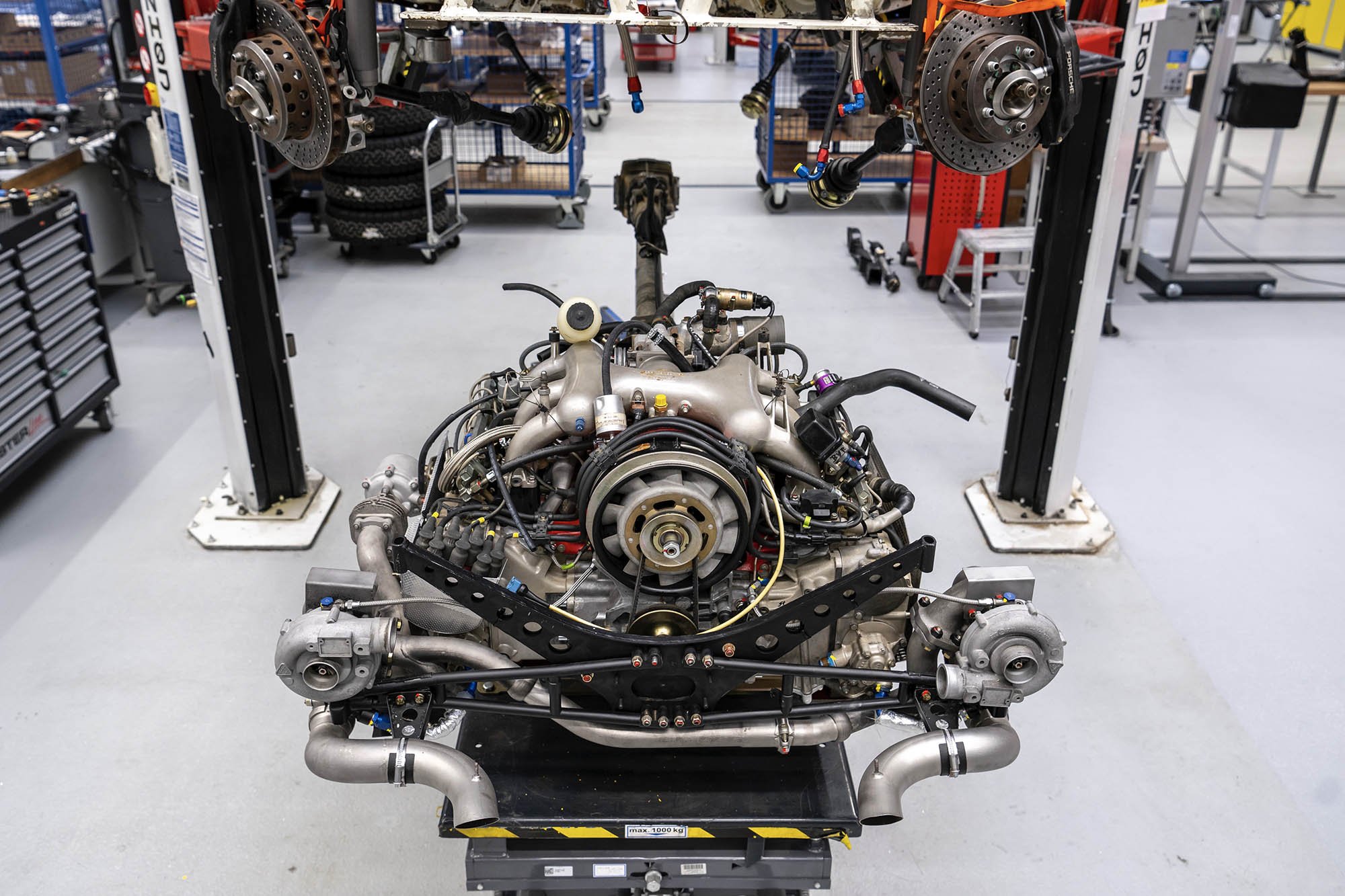

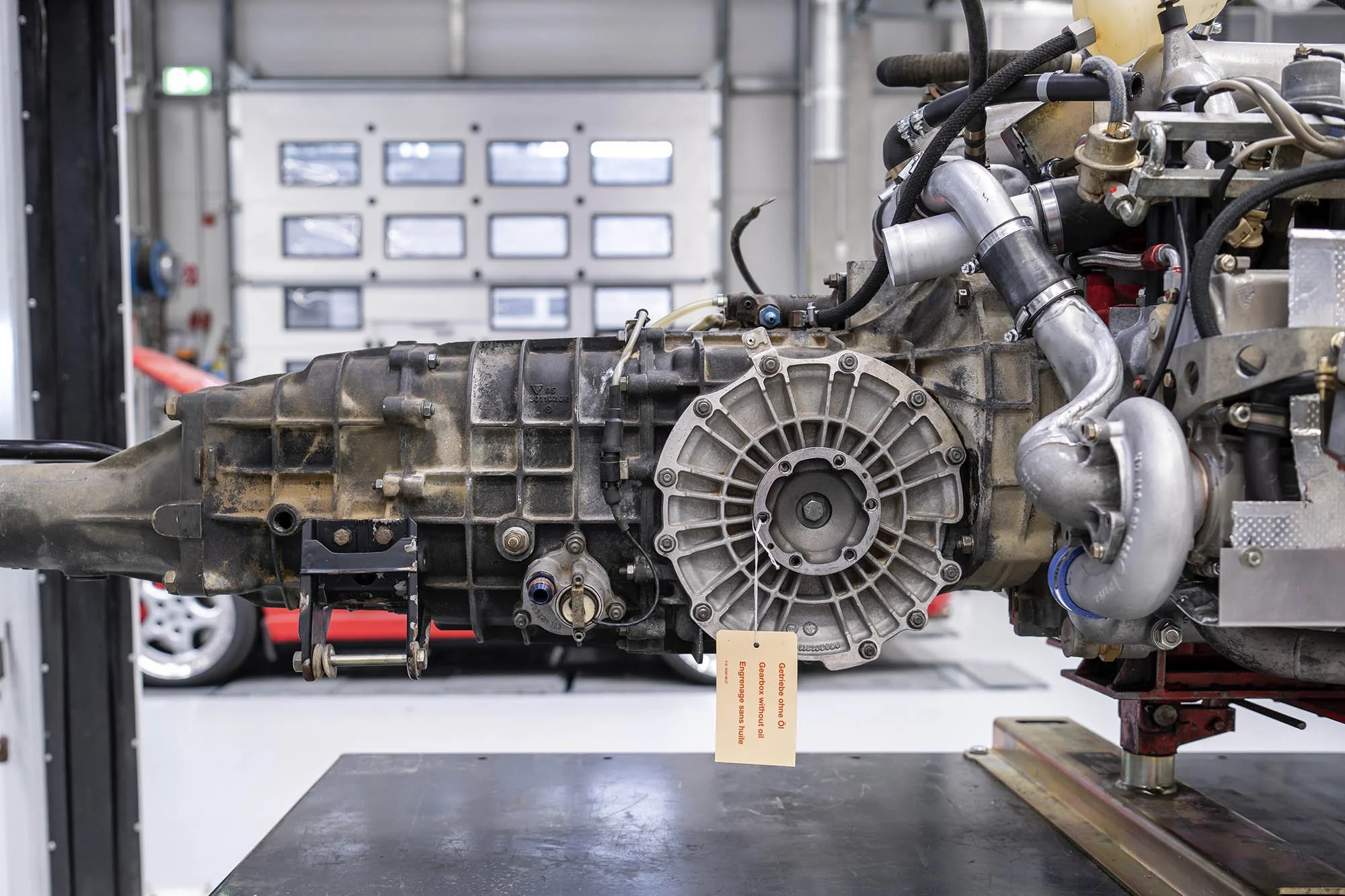

In the 1980s, the team spent two years transforming the 959 into a rally car. The engineers reinforced the suspension with double shock absorbers on the front axle and fitted all-terrain tyres. If the surface didn’t require all-wheel drive, the electro-hydraulically controlled centre differential distributed the power variably between the front and rear axles.

For this gruelling long-distance endurance rally, the sports car manufacturer optimised many features during the 1980s, among them the installation of the engine control units (ECUs). These were positioned high up in the car, to enable it to cross rivers without the ECUs being damaged. Porsche also prepared the oil cooler and oil lines under the rear wings for the rally and transferred motorsport genes into the car by perforating the aluminium support. To reduce the weight further still, the sports car manufacturer punched holes into the brake discs and decided on a body, doors and bonnets made of Kevlar. The experts in Stuttgart therefore achieved a comparatively low dry weight for the car of 1,260 kilograms.

During the 959’s disassembly, the team discovered sand and dirt from the African desert. Since the car’s return from the rally, the body and mechanical parts had never been separated. “As this was not an everyday thing for us, it was fascinating. Muddy dirt showed us today that the 959 Paris-Dakar went through rivers and had experienced water in its interior,” says Werner. Small areas of corrosion where the Kevlar body parts ground against the metal frame as a consequence of the physical pressures of high-speed rally driving were conserved rather than repaired in order to preserve the history of the car.

“We even left the cable ties exactly where they were after testing and overhauling all of the parts. After all, the car’s appearance cannot be recreated.” Gearbox expert Klaus Kariegus is also a fan of the African dust on the car and the authenticity it represents. “The car has proven its quality and durability. Even sand and dust from hard racing use could not harm the technology. High-quality materials were also used back then,” says Kariegus. Makrutzki’s team, which consists of four 959 specialists, looked after the functionality of the technology and the conservation of the historical traces from the rallies. “Only by keeping the damage from back then can we tell the story authentically and preserve it,” Werner concludes.

Photos © Porsche